1.1. Access and Analyse Contents of Textfiles#

Author: Johannes Maucher

Last update: 2024-10-07

In this notebook some important Python string methods are applied. This Python string method documentation provides a compact overview.

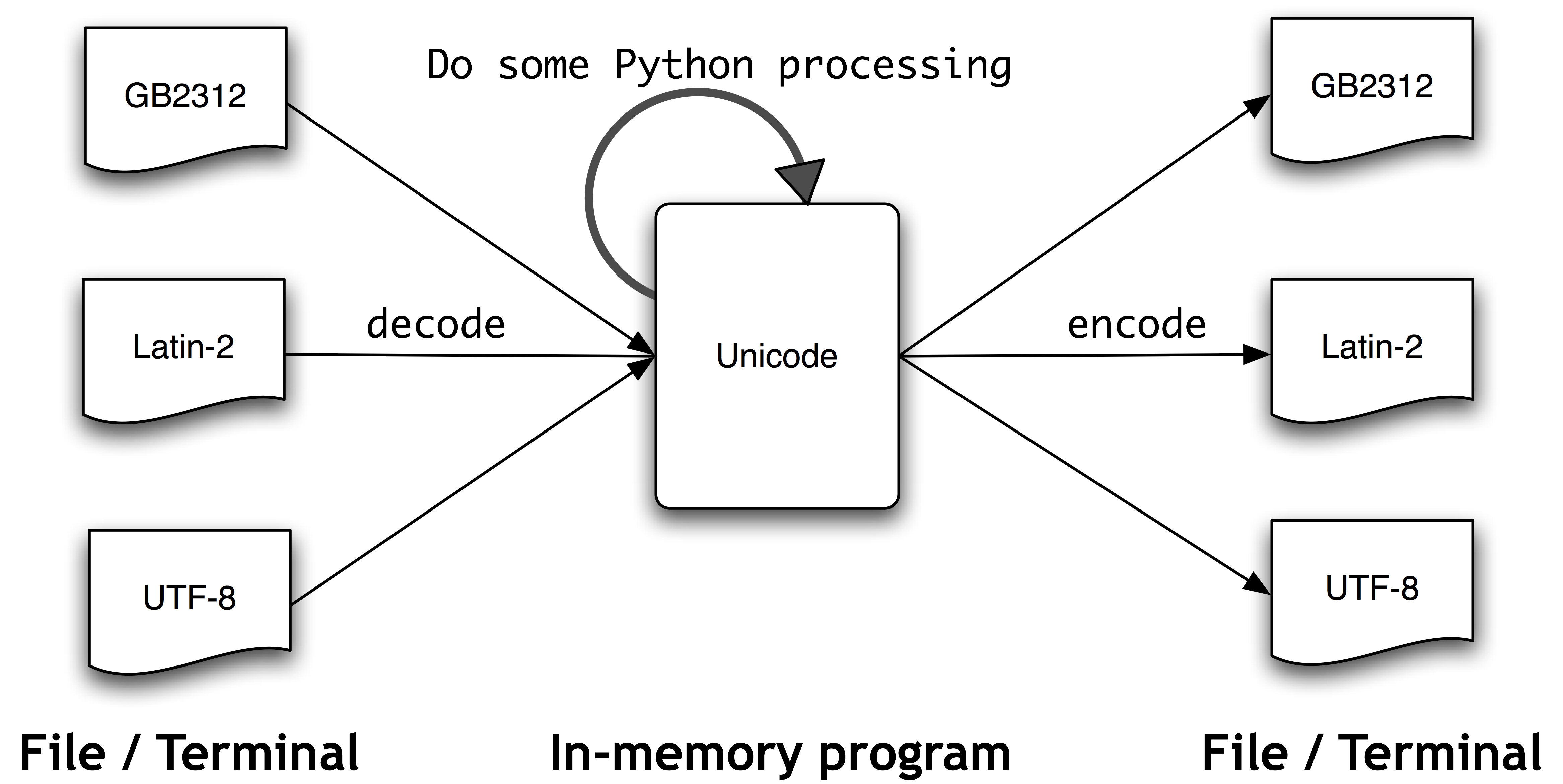

1.1.1. Character Encoding#

In contrast to Python 2.x in Python 3.y strings are stored as unicode, i.e. each string is a sequence of unicode code points. Unicode supports more than 1 million characters. Each character is represented by a code point.

For the efficient storage of strings they are encoded.

A

strcan be encoded intobytesusing theencode()method.bytescan be decoded tostrusing thedecode()method.

Both methods accept a parameter, which is the encoding used to encode or decode. The default for both is UTF-8.

The following code cells demonstrate the difference between strings and bytes:

s1="die tür ist offen"

print(s1)

print(type(s1))

b1=s1.encode('utf-8')

print("After utf-8 encoding: ",b1)

print(type(b1))

b2=s1.encode('latin-1')

print("After latin-1 encoding: ",b2)

print(type(b2))

die tür ist offen

<class 'str'>

After utf-8 encoding: b'die t\xc3\xbcr ist offen'

<class 'bytes'>

After latin-1 encoding: b'die t\xfcr ist offen'

<class 'bytes'>

print("Wrong decoding: ",b1.decode("latin-1"))

print(b2.decode("latin-1"))

print(b1.decode("utf-8"))

#print(b2.decode("utf-8"))

Wrong decoding: die tür ist offen

die tür ist offen

die tür ist offen

1.1.2. Textfile from local machine#

1.1.2.1. Read in row by row#

The following code snippet demonstrates how to import text from a file, which is specified by its path and filename. The example text file is [ZeitOnlineLandkartenA.txt](file://…/Data/ZeitOnlineLandkartenA.txt). In this first snippet the text in the file is read line by line. Each line is stored into a single string variable. The string variables of all lines are stored in a Python list.

listOfLines = []

with open("../Data/ZeitOnlineLandkartenA.txt", "r", encoding="utf-8") as input_file:

for line in input_file:

line = line.strip()

print(line)

listOfLines.append(line)

print(f"\nNumber of lines in this text: {len(listOfLines)}")

Landkarten mit Mehrwert

Ob als Reiseführer, Nachrichtenkanal oder Bürgerinitiative: Digitale Landkarten lassen sich vielseitig nutzen.

ZEIT ONLINE stellt einige der interessantesten Dienste vor.

Die Zeit, in der Landkarten im Netz bloß der Routenplanung dienten, ist längst vorbei. Denn mit den digitalen Karten von Google Maps und der Open-Source-Alternative OpenStreetMap kann man sich spannendere Dinge als den Weg von A nach B anzeigen lassen. Über offene Programmschnittstellen (API) lassen sich Daten von anderen Websites mit dem Kartenmaterial verknüpfen oder eigene Informationen eintragen. Das Ergebnis nennt sich Mashup – ein Mischmasch aus Karten und Daten sozusagen. Die Bewertungscommunity Qype nutzt diese Möglichkeit schon lange, um Adressen und Bewertungen miteinander zu verknüpfen und mithilfe von Google Maps darzustellen. Auch Immobilienbörsen, Branchenbücher und Fotodienste kommen kaum noch ohne eigene Kartenfunktion aus. Dank der Integration von Geodaten in Smartphones werden soziale

Kartendienste immer beliebter. Auch sie nutzen die offenen Schnittstellen. Neben kommerziellen Diensten profitieren aber auch Privatpersonen und unabhängige

Projekte von den Möglichkeiten des frei zugänglichen Kartenmaterials. Das Open-Data-Netzwerk versucht, öffentlich zugängliche Daten zu sammeln und neue

Möglichkeiten für Bürger herauszuarbeiten. So können Anwohner in England schon länger über FixMyStreet Reparaturaufträge direkt an die Behörden übermitteln.

Unter dem Titel Frankfurt-Gestalten gibt es seit Frühjahr ein ähnliches Pilotprojekt für Frankfurt am Main. Hier geht es um weit mehr als Reparaturen. Die Seite soll

einen aktiven Dialog zwischen Bürgern und ihrer Stadt ermöglichen – partizipative Lokalpolitik ist das Stichwort. Tausende dieser Mashups und Initiativen gibt es inzwischen. Sie bewegen sich zwischen bizarr und faszinierend, unterhaltsam und informierend. ZEIT ONLINE stellt einige der interessantesten vor. Sie zeigen, was man mit öffentlichen Datensammlungen alles machen kann.

Number of lines in this text: 11

1.1.2.1.1. Questions#

Run the cell above

with

latin-1-encoding,without setting the

encoding-parameter in theopen()-method.

What happens? A list of codecs supported by python can be found here.

1.1.2.2. Read in text as a whole#

The entire contents of the file can also be read as a whole and stored in a single string variable:

with open("../Data/ZeitOnlineLandkartenA.txt", "r", encoding="utf-8") as input_file:

text = input_file.read()

print(text[:300])

print(f"\nNumber of characters in this text: {len(text)}")

Landkarten mit Mehrwert

Ob als Reiseführer, Nachrichtenkanal oder Bürgerinitiative: Digitale Landkarten lassen sich vielseitig nutzen.

ZEIT ONLINE stellt einige der interessantesten Dienste vor.

Die Zeit, in der Landkarten im Netz bloß der Routenplanung dienten, ist längst vorbei. Denn mit den di

Number of characters in this text: 2027

1.1.3. Segmentation of text-string into words#

The entire text, which is now stored in the single variable text can be split into it’s words by applying the split()-method. The words are stored in a list of strings (wordlist). The words in the wordlist may end with punctuation marks. These marks are removed by applying the python string-method strip().

wordlist = text.split()

print(f"First 12 words of the list: {wordlist[:12]}")

clean_wordlist = [w.strip('().,:;!?-"').lower() for w in wordlist]

print(f"First 12 cleaned words of the list: {clean_wordlist[:12]}")

print(f"Number of tokens: {len(clean_wordlist)}")

print("Number of different tokens (=size of vocabulary): ",len(set(clean_wordlist)))

First 12 words of the list: ['Landkarten', 'mit', 'Mehrwert', 'Ob', 'als', 'Reiseführer,', 'Nachrichtenkanal', 'oder', 'Bürgerinitiative:', 'Digitale', 'Landkarten', 'lassen']

First 12 cleaned words of the list: ['landkarten', 'mit', 'mehrwert', 'ob', 'als', 'reiseführer', 'nachrichtenkanal', 'oder', 'bürgerinitiative', 'digitale', 'landkarten', 'lassen']

Number of tokens: 267

Number of different tokens (=size of vocabulary): 187

1.1.4. Textfile from Web#

#!conda install -y nltk

from urllib.request import urlopen

import nltk

import re

Download Alice in Wonderland (Lewis Carol) from http://textfiles.com/etext:

alice_url = "http://textfiles.com/etext/FICTION/alice.txt"

alice_raw = urlopen(alice_url).read().decode("latin-1")

print("Print a short snippet of downloaded text:")

print(alice_raw[2710:3500])

Print a short snippet of downloaded text:

THE MILLENNIUM FULCRUM EDITION 2.7a

(C)1991 Duncan Research

CHAPTER I

Down the Rabbit-Hole

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister

on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had

peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no

pictures or conversations in it, `and what is the use of a book,'

thought Alice `without pictures or conversation?'

So she was considering in her own mind (as well as she could,

for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether

the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble

of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White

Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

There was no

Save textfile in local directory:

with open("../Data/AliceEnglish.txt","w") as output_file:

output_file.write(alice_raw)

Read textfile from local directory:

with open("../Data/AliceEnglish.txt", "r", encoding="latin-1") as input_file:

text = input_file.read()

print(text[2710:3500])

print(f"\nNumber of characters in this text: {len(text)}")

THE MILLENNIUM FULCRUM EDITION 2.7a

(C)1991 Duncan Research

CHAPTER I

Down the Rabbit-Hole

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister

on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had

peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no

pictures or conversations in it, `and what is the use of a book,'

thought Alice `without pictures or conversation?'

So she was considering in her own mind (as well as she could,

for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether

the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble

of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White

Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

There was no

Number of characters in this text: 150886

1.1.5. Simple Methods to get a first impresson on text content#

In a first analysis, we want to determine the most frequent words. This shall provide us a first impression on the text content.

1.1.5.1. Questions:#

Before some simple text statistics methods (word-frequency) are implemented inspect the downloaded text. What should be done in advance?

1.1.5.2. Remove Meta-Text#

The downloaded file does not only contain the story of Alice in Wonderland, but also some meta-information at the start and the end of the file. This meta-information can be excluded, by determining the true start and end of the story. The true start is at the phrase CHAPTER I and the true end is before the phrase THE END.

start_of_book = alice_raw.find("CHAPTER I")

end_of_book = alice_raw.find("THE END")

print(f"Start: {start_of_book:>7}")

print(f"End: {end_of_book:>7}")

alice_raw = alice_raw[start_of_book:end_of_book]

Start: 2831

End: 150878

1.1.5.3. Tokenisation#

Split the relevant text into a list of words:

import re

alice_words = [word.lower() for word in re.split(r"[\s.,;´`:'()!?\"-]+", alice_raw)]

#alice_words = [word.lower() for word in re.split(r"[\W`´]+", alice_raw)]

#alice_words =["".join(x for x in word if x not in '?!().´`:\'",<>-»«') for word in alice_raw.lower().split()]

#alice_words =["".join(x for x in word if x not in '?!.´`:\'",<>-»«') for word in alice_raw.lower().split()]

1.1.5.4. Generate Vocabulary and determine number of words#

num_words_all = len(alice_words)

print(f"Number of words in the book: {num_words_all}")

alice_vocab = set(alice_words)

num_distinct_words = len(alice_vocab)

print(f"Number of different words in the book: {num_distinct_words}")

print(f"In the average each word is used {num_words_all / num_distinct_words:2.2f} times")

Number of words in the book: 27341

Number of different words in the book: 2583

In the average each word is used 10.58 times

1.1.5.5. Determine Frequency of each word#

from collections import Counter

word_frequencies = Counter(alice_words)

word_frequencies.most_common(20)

[('the', 1635),

('and', 872),

('to', 730),

('a', 630),

('it', 593),

('she', 552),

('i', 543),

('of', 513),

('said', 461),

('you', 409),

('alice', 397),

('in', 366),

('was', 356),

('that', 316),

('as', 263),

('her', 246),

('t', 218),

('at', 211),

('s', 200),

('on', 194)]

1.1.5.6. Optimization by stop-word removal#

Stopwords are words, with low information content, such as determiners (the, a, …), conjunctions (and, or, …), prepositions (in, on, over, …) and so on. For typical information retrieval tasks stopwords are usually ignored. In the code snippet below, a stopword-list from NLTK is applied in order to remove these non-relevant words from the document-word lists. NLTK provides stopwordlists for many different languages. Since our text is written in English, we apply the English stopwordlist:

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

stopword_list = stopwords.words('english')

alice_words = [word.lower() for word in alice_words if word not in stopword_list]

num_words_all = len(alice_words)

print(f"Number of words in the book: {num_words_all}")

alice_vocab = set(alice_words)

num_distinct_words = len(alice_vocab)

print(f"Number of different words in the book: {num_distinct_words}")

print(f"In the average each word is used {num_words_all / num_distinct_words:2.2f} times")

Number of words in the book: 12283

Number of different words in the book: 2437

In the average each word is used 5.04 times

Generate the dictionary for the cleaned text and display it in an ordered form:

word_frequencies = Counter(alice_words)

word_frequencies.most_common(20)

[('said', 461),

('alice', 397),

('little', 128),

('one', 103),

('know', 88),

('like', 85),

('would', 83),

('went', 82),

('could', 77),

('queen', 75),

('thought', 74),

('time', 71),

('see', 68),

('well', 63),

('king', 63),

('*', 60),

('began', 58),

('turtle', 58),

('way', 57),

('hatter', 56)]

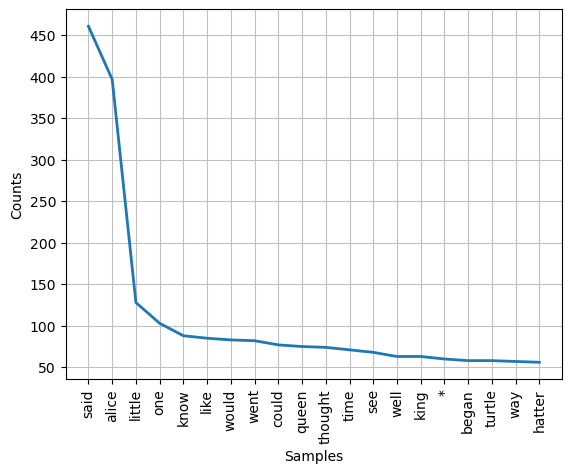

Another option to calculate the word frequencies in an ordered manner is to apply the nltk-class FreqDist.

fd = nltk.FreqDist(alice_words)

fd.plot(20)

<Axes: xlabel='Samples', ylabel='Counts'>

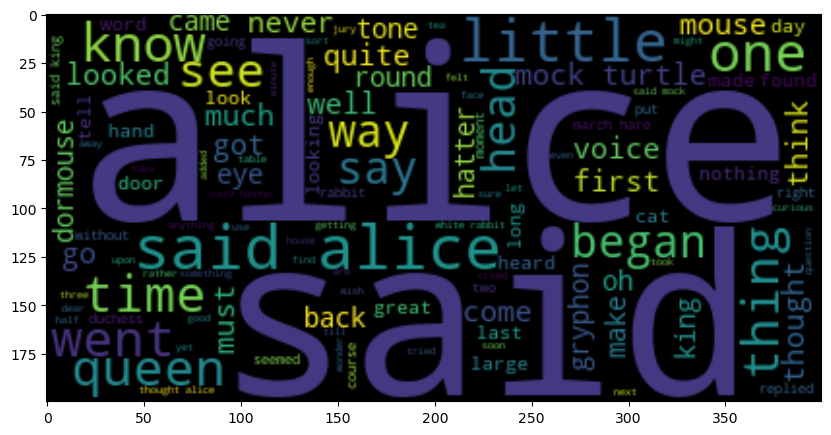

1.1.5.7. Word Cloud#

Run pip install wordcloud, then run the following code.

#!pip install wordcloud

from wordcloud import WordCloud

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

wc=WordCloud().generate(" ".join(alice_words))

plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

plt.imshow(wc, interpolation="bilinear")

<matplotlib.image.AxesImage at 0x142f87150>